By Dennis Pagen

Originally published in USHPA Pilot, May/June 2019

Free flying is a personal thing. Maybe we hitch a ride up to takeoff, maybe we get a little assistance launching, maybe we get a helping hint from a spiraling hawk, but in the main we fly alone, making our own decisions. Yet, early on in our flying progress we learn to thermal followed by the quick realization that thermals are finite, periodic, occasional, elusive and thus open game. That means if we are going

to experience some of the most fun in human endeavors--thermaling--we will be joined by other pilots in the air in the same lift blob.

I once flew with a pilot who was so uncomfortable with other gliders anywhere near, he would leave every time another pilot came to share his lift, even a couple hundred feet above or below him. That pilot arrested the development of his skills and often had very short flights. Perhaps some reader has this tendency, but there is hope: This article is all about the methods of thermaling with other pilots, be they of your ilk (tubes or lines) or different (lines or tubes).

The Problems

Hopefully we all have a healthy dose of respect for the pitfalls (and falls) of flying. We should be wary of midairs and potential conflicts. But abject and unfounded fears in any aspect of life is counter-productive. Phobias, prejudices and bouts of illogic are debilitating and always prevent us from reaching our full potential. Unfounded or foolish fears can best be over-come through desensitization and education. Desensitization requires gradual exposure, and education starts right here.

Look at this: Nearly everyone reading this piece drives a car, with other drivers zooming by on the highway, or milling through traffic in a busy city. Some of the other drivers may even be impaired by drugs, sex or rock ’n’ roll (no, never us). Yet, by being aware, awake, courteous and observant of some easy traffic rules, we never (or rarely) have an accident.

The main difference in piloting a glider in a swarm and driving a car in traffic is that in a glider we are dealing with three dimensions, while in a car we are mostly concerned with two dimensions. The additional dimension is up and down, of course, and really, this isn’t a problem with new pilots because there usually aren’t thick swarms of pilots outside of competition, and in our early practice we expect to only fly with one other pilot in a thermal. However, to our benefit the speeds involved with our type of flying are mostly half or less than the speeds when driving a car. The work load isn’t all that bad.

Flying, like driving, has rules and requires consideration of the other pilots when we work in proximity. But the flying rules aren’t nearly as many or complex as driving rules. So let’s get to it.

Approaching and Entering a Thermal

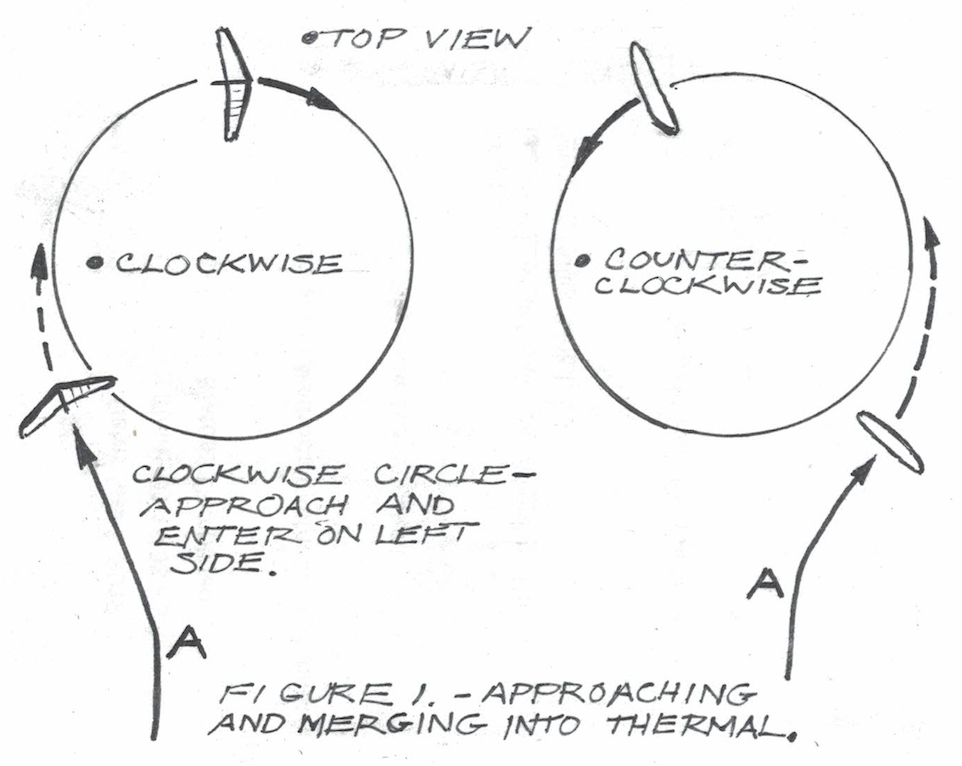

One of the important parts of thermaling with another pilot is joining him or her in a manner prone to instill confidence as well as avoiding making the other pilot alter his or her path around the thermal circle. The best way to begin instilling confidence is to approach the thermaling pilot on the correct side with a wide enough clearance path that the other pilot doesn’t feel threatened by your approach. This process is best shown in an illustration. Figure 1 shows the thermaling pilot in an established circle (we show both clockwise and counterclockwise directions for clarity). You should be able to see that if you approach a clockwise circling pilot you must join the circle from the left side to initiate a right turn and duplicate the circle. Vice-versa for a counterclockwise circle. Look at the figure and note the point labeled A. That point is where an approaching pilot alters his path to get to the correct side of the thermal circle. This point A can be a quarter mile away, or further, of course. However, in thermal conditions the approach path is apt to be altered by turbulence somewhat. But more importantly, if you come from quite a distance on a beeline, the circling pilot has no idea if you see him/her or not. On the other hand, a straight approach to the thermal is usually most efficient (given we cannot know exactly how the sink is distributed) and making a definite course alteration at point A is a clear signal that you see the other pilot and are properly positioning yourself to enter the established circle with ample safety margins.

How far away from the circle should point A be? The answer depends on your skill and that of the circling pilot. In a competition where most pilots are highly skilled and comfortable thermaling with others, point A may be only a few wingspans from the circle for hang gliding and even less for paragliding. However, for recreational pilots, 5 to 10 wingspans (50 to 100 yards) is reasonable. Wallowing around as you approach the circle sends the wrong message, so a straight, fast flight and a definite course change at A is key to good messaging, good manners and good safety. Note that sink generally surrounds a thermal so you would normally want to fly fast and straight to minimize your time in it. On the other hand, sometimes you encounter an associated thermal core before you get to the established circle. If you are outside the A point, there is no real harm in trying out this core. However, in my experience in competition, good pilots are usually in the best core and nearby cores are a waste of time. In recreational flying that may not be the case, but you can always come back for the errant core if the marked core does not pan out.

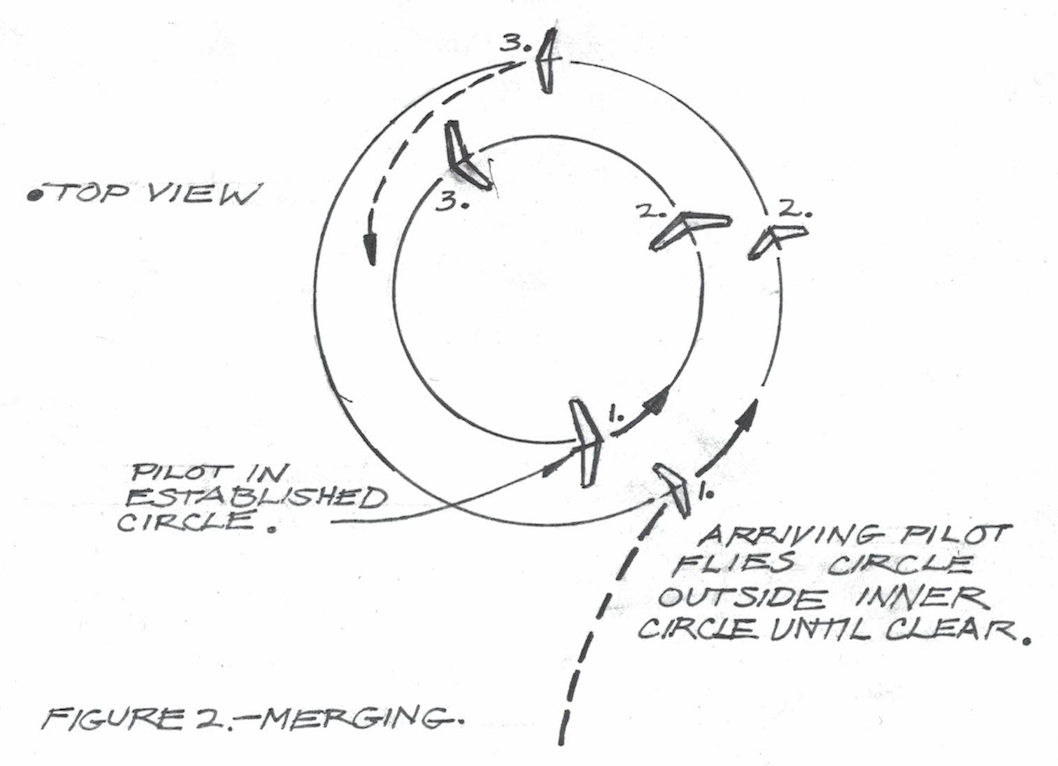

From the figure you can see that we should enter the thermal at a tangent to the circle. Such a practice requires that you mark where that tangent is when the established pilot is on that side of the circle. It’s not hard to see where that tangent point is with a little practice, even in wind with a drifting thermal, because you are drifting too. Of course, we should be aware that when our path reaches the circle, the other pilot may be right where we wanted to enter the circle. In that case, we should simply make a wide circle around the established circle as shown in figure 2. Because the pilot in the thermal has a much smaller circle, he will soon get ahead of us and we can then nudge our glider over to enter the circle. The nudge should be timed to put you in the circle exactly opposite the other pilot, as shown. The main point here is to allow plenty of clearance for safety and to allow the other pilot to maintain his circle, for if he’s reasonably good he will be in the best part and we want to join him. If we knock him out it’s bad karma, but also less efficient for us if we have to search for the best track in the core.

It should go without saying (but we’ll say it because it is too common a defect) that we all need to be as comfortable entering a circle turning clockwise as counterclockwise. If you are not, you have a summer project. The best way to familiarize yourself with melding into all circles is to practice with a friend on bicycles. Have the friend establish a steady circle while you try to enter it smoothly with no conflict--in both directions. This is the best way to learn thermal basics in a comfortable environment.

Working Together

If you are the pilot in the established circle you have a small responsibility. Mainly, don’t go to sleep. Be vigilant so you are aware of approaching pilots. In moving or variable thermals we often alter our circle to remain in the best lift, but with a nearby pilot about to meld into our circle we best keep our circle regular, at least for a couple turns until the other pilot gets established. But whatever you do, don’t flatten out your bank and widen the circle. This is a beginner reaction and understandable if we are timid, but such behavior is confusing for everyone. It puts you out of the best lift and the newly arrived pilot will not know where to anchor his circle. If he is good he will have a tendency to establish immediately in the best circle and may come into conflict with you at some point in your mutual circles. In other words, by flattening out (through misplaced caution) you actually cause more conflicts and reduce safety. Keep your circle steady and your position predictable.

It should be noted that new thermal pilots in general make circles too big for best efficiency (climb rate). You may find a very good pilot entering your circle and wanting to tighten it up. He may do it by staying a little inside your circumference, and in which case he will be catching up to you. If that happens you can tighten up and climb together. If you don’t he may eventually go inside you and climb away. That leaves you in the dregs of the thermal, but more importantly may make you feel that you got a little close as he blows by you. The best practice is to be aware and try to duplicate the other pilot’s path if you know he is a good pilot.

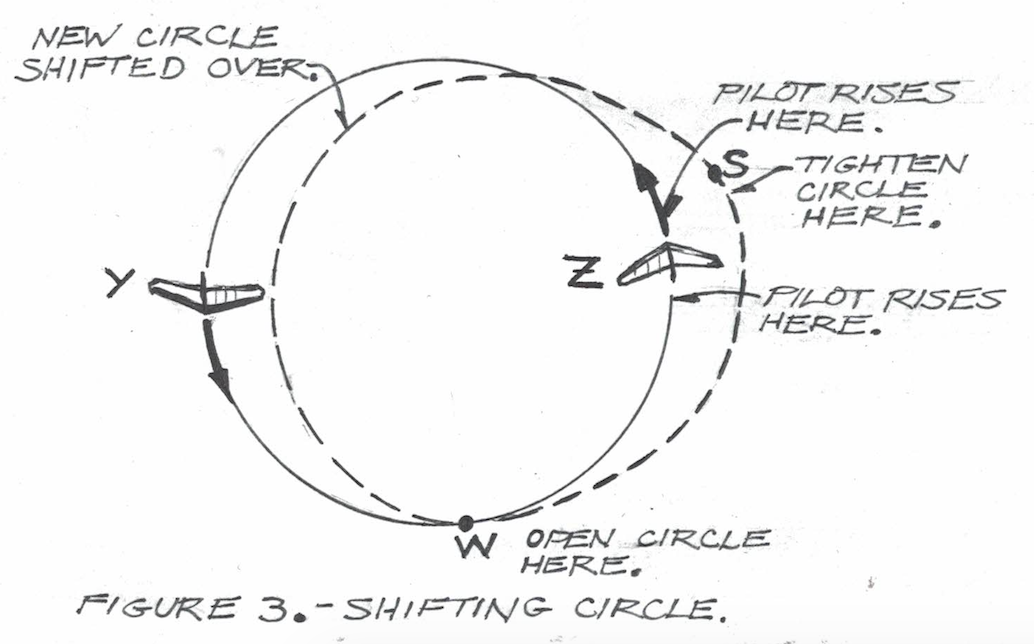

If a thermal is moving or broken, generally two pilots can work it better than one. This factor harkens back to our main point that we all should be ready and able to work a thermal with another capable pilot. If the other pilot is about opposite to you, you have at least 10 seconds to see what the air is doing where he is at, and act accordingly. For example, in figure 3 assume you are at point Y and the other guy is at Z. Imagine you see him rise in relation

to you. The main reason that happens is he passed through a patch of better lift. Thermals often display surges and unsteady flow, which isn’t a mystery since they can be a roiling, rolling plume like smoke from a stack. Or think about the tumbling action we see in vigorous cumulus clouds which are caused by thermals (cumulus means tumbled in Latin).

When you see the pilot rise, in most cases you should alter your circle to put yourself more in the lifting area. To make this adjustment, simply widen your circle (open up or bank less) at point W in the figure, then steepen your bank again to reestablish the same bank angle at point S--about 90 degrees around the circle from W. You have now just shifted your circle towards the better lift. If your thermal-mate is adept, he will do the same thing when he comes around. There are times when a thermal is so mercurial that a couple pilots may be constantly adjusting position to max out the climb. It becomes a pas de deux.

We wish to emphasize that if you are alone in a surging thermal, you may do a reasonably good job at staying in the best lift, but you cannot do it as efficiently as you can when another pilot is there to indicate where the best lift is only a half circle ahead of you. Alone you may tighten up when you feel a surge, but it usually takes a full circle to really center on it, and if the thermal is continuously changing, it may be blossoming elsewhere by then.

Just as with merging into an occupied thermal, you can best practice this coordinated moving of circles on bicycles with a buddy clued in to what you are doing. Imagine him hitting a surge of lift, then move over to center on it with him altering his circle to join you. Then have him do the move first, and you follow. It should be noted that good pilots follow the same procedures when a patch of sink is encountered in the thermal. In this case you move away from it by tightening your circle up for about 90 degrees, then opening it up again. Practice this thermal technique as often as possible and it will become second nature.

Hang and Para Guiding

Now here’s a guide for hang glider pilots merging, melding and mixing with paraglider pilots and vice versa. Hang gliders thermal at speeds around 30% to 50% faster than paragliders. That means potential conflicts in a shared thermal. In addition, hang gliders cannot maneuver as quickly as paragliders, paragliders occupy more vertical airspace and, finally, hang glider pilots have less visibility than paragliding pilots, especially upwards.

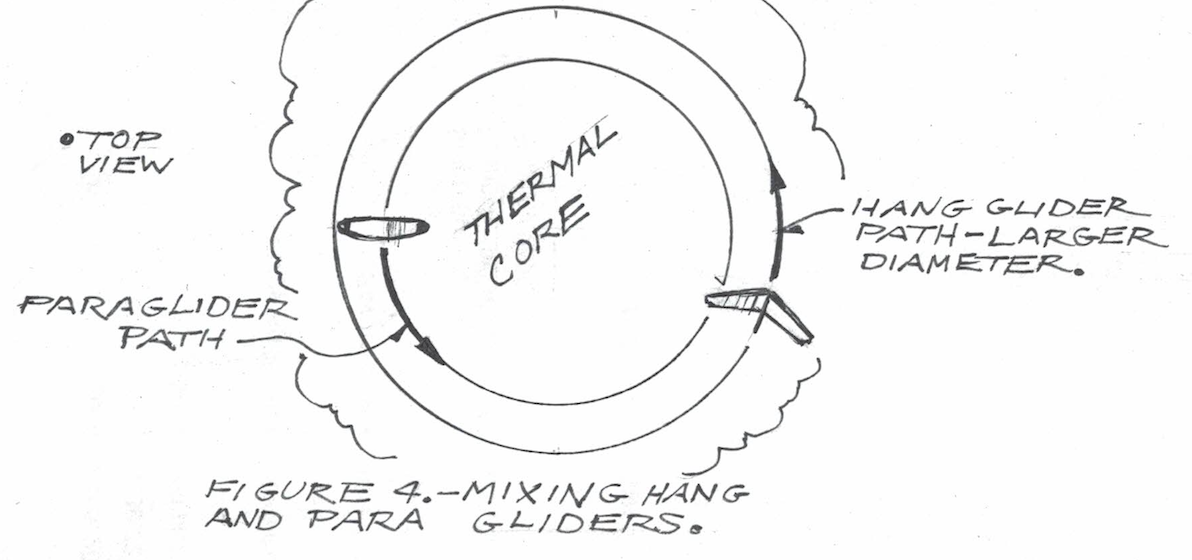

With all these considerations, let’s see how to operate together. The most important matter we need to resolve is the different thermaling speeds of paragliders and hang gliders. The only way to make this work without a lot of weaving in and out (less safe) or one pilot getting knocked out of the thermal (unfriendly and frustrating) is for the two different gliders to fly two different size circles. As figure 4 shows, when the slower paraglider flies a smaller diameter circle, he travels a shorter route, so the two gliders with mismatched airspeeds can stay directly across from each other and not conflict. Years of experience has shown that this scheme is the only one that works effectively.

There are two behaviors to overcome with this method. First, paraglider pilots often tend to make wide circles when thermaling, perhaps because they learned in big, wide thermals and never graduated to being efficient

in tighter cores. There is nothing detrimental in turning tighter in a paraglider if you know how to avoid a stall and spiral. In fact, the added G-loading and airspeed in a tight turn may provide more pressurization. If you don’t tighten up, an experienced hang glider pilot may have the tendency and temptation to cut inside of you and confusion will follow. Note: Pilots on the same type of glider (hang or para), but of different performance levels should be aware of these different thermaling speeds as well. For example, I have seen many pilots on intermediate gliders thermaling with wide circles while a pilot on a competition wing tries to work the same lift. Usually the tendency is for the faster comp pilot to cut inside the inter- mediate guy boating around, thereby causing the slow pilot to lose the core and feel imposed upon. But if you tighten up, you’ll find the conflicts largely go away and you’ll climb faster.

The second matter in this regard is that neither pilot may be in the ideal circle for his or her glider, but still it is better to be going up than getting blocked out of the thermal and causing animosity. I have seen many pilots lose the lift because neither would coordinate nor cooperate.

Another important factor for everyone to understand is that hang glider pilots cannot see across the circle when they are banked up steeply. In fact, the way a good pilot operates is to maintain a regular circle and trust the other pilot to do the same. This procedure works for a mixed hang and para pilot combo as well. If both are maintaining the circle diameters that keep them on opposite sides of the circle, safety and performance are maximized.

The next matter to consider is merging into an established gaggle in mixed company. As described above, a straight-in approach with a definite signaling path change at point A is the proper method. Hang glider pilots should make this change earlier than paraglider pilots as befits their less maneuverable nature. But if the hang glider pilot is in the established circle, paraglider pilots should make the change sooner than normally, at least until the hang glider pilot gets used to you working closer. While you work a thermal together you can learn the quality of each other’s experience.

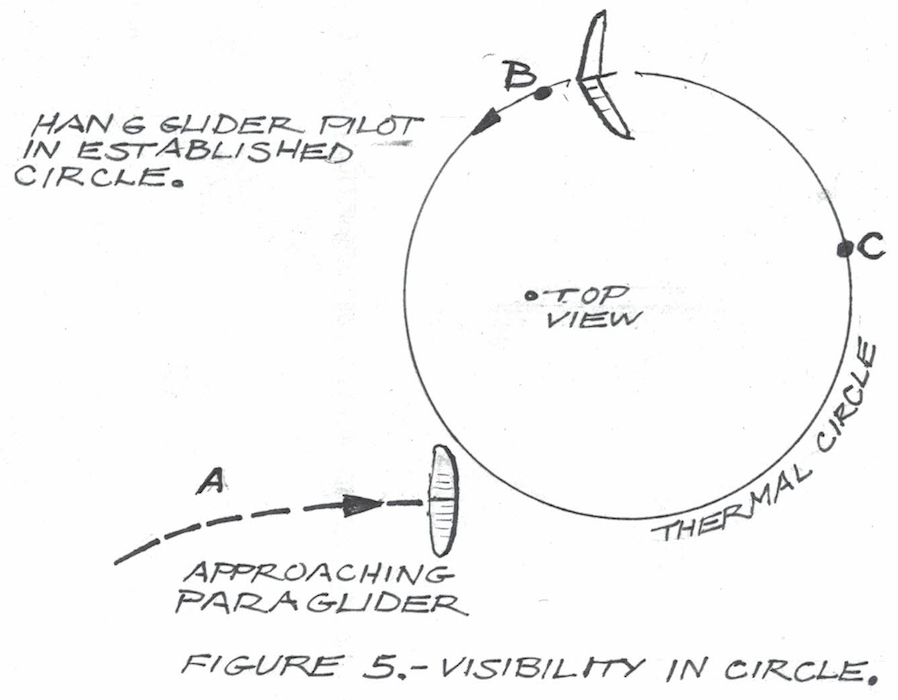

In figure 5 we show a top view of a paraglider approaching a circling hang glider. The para- gliding pilot must be aware that a prone hang glider pilot cannot see the approach clearly until his circle reaches point B in the diagram. In fact, point B is where a hang glider pilot decides whether or not to continue the circle around according to the clearance he has to the approaching glider. It is when the circling pilot is at B that you should make the definite course alteration to go around the circle and merge (this principle applies to both types of gliders). Obviously you can change your path much sooner, but you will disappear to the hang glider pilot and he may widen his circle and no longer be in, or mark, the best lift. A paraglider pilot who is alertly looking around can see an approaching pilot sooner--at C, for example--so making the course change earlier in an approaching hang glider is appropriate.

Finally we should give a reminder that the lower pilot has the right of way. If another pilot is climbing up to you, you have to give way. The best method in this case is to simply widen your circle and let him play through. Once he is clear above you can tighten back up and resume your good coring. In many thermals paragliders can work more efficiently, so hang glider pilots will have to give way and should be aware that paragliders require more vertical airspace clearance--more than twice that of a hang glider. In all cases, discussion and review of the flight with the pilot you shared a thermal with helps educate you both and helps you work together better during the next flight.

The current state of flying with its dwindling sites and crowding airspace means we all have to learn to mix, no matter what our wing preference. In order to mix we have to merge and meld properly and predictably. A good dose of courtesy helps to smooth the waters, and goddess or goodness knows, we all need each other to keep our sports viable. Cooperate and elevate.